Studies have shown that there is no significant difference in the prevalence of eating disorders across ethnic groups and that there are more shared risk factors among people of all ethnic groups than differences.1

Still, this doesn’t mean that the experience of struggling with an eating disorder is similar across all ethnic groups. Eating disorders may be disproportionately overlooked in people of color, even by medical professionals. Some research has shown doctors are less likely to diagnose eating disorder symptoms in people of color or are less likely to offer resources or treatment options.2

This is just one reason why it’s especially important to understand how eating disorders affect people of color and to learn more about how to find the proper help for overcoming these dangerous conditions.

Stats & Facts on Eating Disorders Among People of Color

Statistics regarding how eating disorders affect people of color likely have some inaccuracies due to low reporting and under-diagnosis of eating disorders in these demographics. People of color also often face higher levels of stress and additional barriers to treatment, which can also impact reported rates.

Still, the statistics that have been collected by eating disorder specialists reveal some patterns:3

- African Americans are less likely than white Americans to be diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, but when they do receive a diagnosis, they generally struggle with it for longer.

- Asian American college students have higher rates of body dissatisfaction than their non-Asian BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) peers.

- Asian American college students have higher rates of food restriction than their white peers.

- Asian American college students have higher rates of cognitive restraint, muscle building, and purging than both their white and non-Asian BIPOC peers.

- Black teenagers are twice as likely as white teenagers to engage in bulimic behavior, such as binging and purging.

- Hispanic teenagers are more likely than non-Hispanic teens to have bulimia nervosa.

- People of color are 50% less likely to receive an eating disorder diagnosis or receive eating disorder treatment than white people.

Again, a majority of research on eating disorders has been conducted on white girls and women. While current research works to include more racial and ethnic groups, it is still far from fully representative.

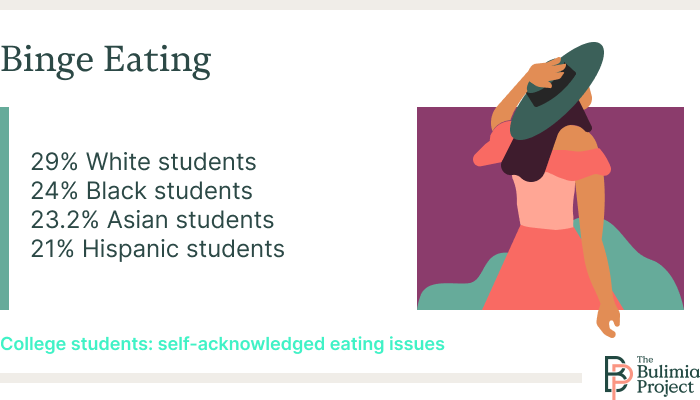

Eating Disorder Rates Among College Students

Another study of university students was conducted to look for any patterns in who would develop eating disorders, as well as the prevalence of disturbed eating patterns across different ethnic demographics.

Researchers asked students for self-acknowledged eating issues, including struggles with a probable or definite disorder. If a student self-identified as struggling with disordered eating behaviors, they were asked which disorder they believed they had.

Findings included: [4]

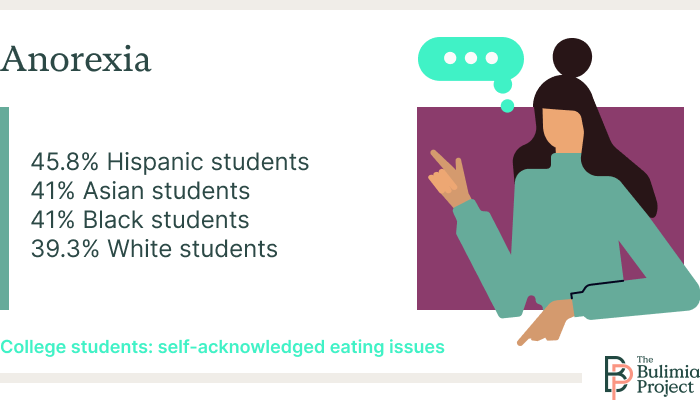

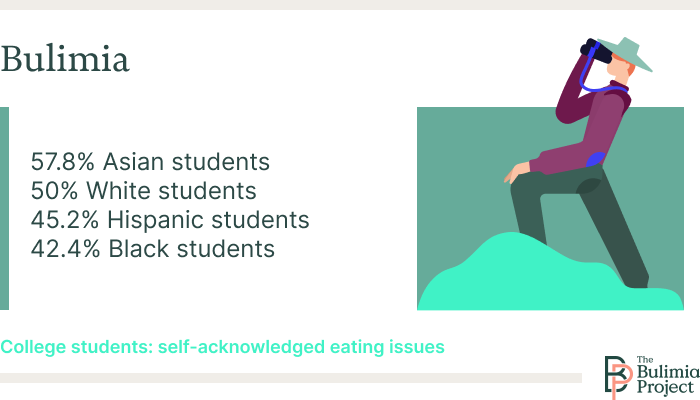

- White students:

- 39.3% with anorexia nervosa

- 50% with bulimia nervosa

- 29% with binge eating disorder

- Black students:

- 41% with anorexia nervosa

- 42.4% with bulimia nervosa

- 24% with binge eating disorder

- Asian students:

- 41% with anorexia nervosa

- 57.8% with bulimia nervosa

- 23.2% with binge eating disorder

- Hispanic students:

- 45.8% with anorexia nervosa

- 45.2% with bulimia nervosa

- 21% with binge eating disorder

While imperfectly measured, these statistics still work to illustrate that it is not only white women struggling with eating disorder symptoms or other unhelpful thoughts and behaviors.

Causes & Issues Related to Eating Disorders Among People of Color

Eating disorders can be caused by various factors, including genetic, environmental, biological, behavioral, cultural, social, and psychological influences. Indeed, it is rarely a single cause but a combination of these factors that leads to the onset of an eating disorder.

However, which of these elements represents the biggest risk factors can vary and is often influenced by someone’s gender or ethnicity.

For many people of color, environmental stressors present a particular challenge. Many people of color carry high levels of stress or trauma related to experiences of racism and acculturation. And this type of stress can work to trigger eating disorder behaviors.5

Among people of color, some specific ethnic differences have also been found that contribute to the onset of an eating disorder.

Potential Risk Factors for Asian Americans

Across some studies, Asian American women have reported higher levels of thin-ideal internalization than their non-Asian peers.3

Asian American college students have higher rates of body dissatisfaction.3

While research connecting this trait to the development of eating disorders is scant, it’s thought that higher levels of thin-ideal internalization among Asian American women have led this group to struggle with eating disorders at a higher rate than other women of color.6

Potential Risk Factors for African Americans

Research examining the impact of beauty ideals across cultures has shown that Black women generally have a more favorable or accepting view toward larger bodies, express less concern about diet, and showcase more body satisfaction than white women.7

Still, some newer studies have taken a different tack, utilizing different frameworks that do not directly compare the attitudes of Black women and white women. These studies found that societal beauty standards can negatively impact African American women and that the more time they spend around traditional Western culture and media, the greater their levels of body dissatisfaction.7

Potential Risk Factors for Latinx Americans

Specific studies on how cultural, social, and environmental factors may impact Latinx people are also sparse, but anecdotal evidence of these cases has been shared among doctors.

Some mental health experts say that Latinx women, in particular, may experience outsized isolation within their family unit, making it more difficult to reach out for help. Latinx-American women may also struggle with conflicting beauty standards within a culture that generally celebrates larger bodies but a society that overall celebrates thinness.8

Barriers to Treatment for People of Color

On top of the different experiences that may trigger or maintain patterns of disordered eating among people of color, various barriers to treatment may also present themselves when compared to white people who seek treatment for these conditions.

A majority of research on eating disorders has been conducted on white women, which may be part of the reason why they are stereotyped as the people who routinely struggle with these conditions. Regardless, these stilted studies and statistics fail to accurately describe the experiences of people of other ethnicities and genders, which can present itself in the way people are diagnosed with eating disorders.

Black women are 25% to 45% less likely to be diagnosed with an eating disorder.

Overall, Black women are anywhere from 25% to 40% less likely to receive eating disorder diagnoses than white women, according to one doctor’s estimate.9 In some cases, a medical professional may fail to screen people of color for eating disorders, even in the face of more obvious symptoms.

Cultural expectations and social norms within ethnic minorities can also present treatment roadblocks. Getting help may be considered a sign of weakness, or women may feel conflicted, as larger bodies may generally be more celebrated within their culture, but make them feel separated from more Westernized beauty ideals.8

Finding Help for an Eating Disorder

When disordered eating habits lead to an eating disorder, it is time to seek professional help. These conditions can be dangerous or even deadly if left untreated, so the earlier help is sought, the better the potential for long-term recovery.

Unfortunately, people of color may need to advocate for themselves more in these instances, as eating disorder symptoms have historically been overlooked in this population.

Recognizing that a problem exists is an important first step. If you think you or your loved one might have an eating disorder, talk to your doctor. Be firm and ask for resources and referrals.

Within Health offers personalized remote eating disorder treatment backed by years of experience.

Within’s IOP and PHP programs offer meal kit deliveries, a numberless scale, a convenient app to attend therapy sessions and view your schedule, and so much more.

Call for a free consultation

Treatment may be provided in various settings, varying in intensity and structure based on the needs of the individual. This can range from hospitalization to outpatient programs.

Lately, there has also been a movement toward introducing treatment programs with an eye toward greater inclusiveness and incorporating treatment specifically for people of different ethnicities, gender identities, or cultural backgrounds.

If you or a loved one are struggling with an eating disorder, reaching out to your primary care doctor or mental health therapist is a good first step toward finding the kind of treatment that will help you walk the path to recovery and build a healthier, happier future.

Resources

- Cheng ZH, Perko VL, Fuller-Marashi L, Gau JM, & Stice E. (2019). Ethnic differences in eating disorder prevalence, risk factors, and predictive effects of risk factors among young women. Eating behaviors; 32:23–30.

- Gordon KH, Brattole MM, Wingate LR, & Joiner TE Jr. (2006). The impact of client race on clinician detection of eating disorders. Behavior therapy; 37(4):319–325.

- Eating Disorder Statistics. (2021). National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders. Retrieved September 2022.

- Sala M, Reyes-Rodríguez ML, Bulik CM, & Bardone-Cone A. (2013). Race, ethnicity, and eating disorder recognition by peers. Eating disorders; 21(5):423–436.

- People of Color and Eating Disorders. (2022). National Eating Disorders Association. Retrieved September 2022.

- Akoury L, Warren C, Culbert K. (2019, September 4). Disordered Eating in Asian American Women: Sociocultural and Culture-Specific Predictors. Frontiers in Psychology; 10.

- Awad GH, Norwood C, Taylor DS, Martinez M, McClain S, Jones B, Holman A, & Chapman-Hilliard C. (2015). Beauty and Body Image Concerns Among African American College Women. The Journal of Black Psychology; 41(6):540–564.

- Fuller K. (2019, February 28). We Are Failing at Treating Eating Disorders in Minorities. Psychology Today. Retrieved September 2022.

- Nawaz A, Lincoln Estes D. (2022, March 28). People of Color with Eating Disorders Face Cultural, Medical Stigmas. PBS. Retrieved September 2022.